Josh Ritter Album Club! (group conversation and interview)

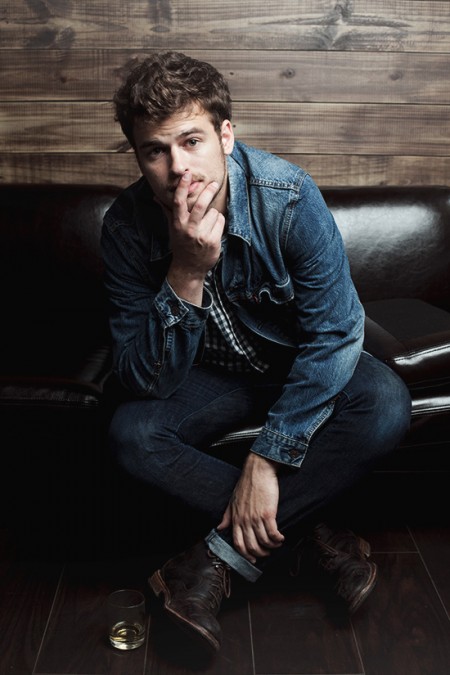

Last weekend I made up a big crockpot of stew and invited ten Fuel/Friends readers over to my house to talk about Josh Ritter‘s new album, The Beast In Its Tracks, an intensely personal record that Josh wrote in the wake of his recent divorce. The concept behind this pow-wow was that in the same way people get together to talk about books they’ve read and been affected by, it would be interesting to try extending the same concept to the music we so passionately consume.

And passionately do Josh’s fans consume his music. I got over forty entries for this album club in just a couple of days, from as far away as France and England. People wrote long, beautiful, wrenching letters to me about Josh’s music and how it had soundtracked some of their most excoriating moments and months in their lives, as well as some of the most joy-filled. Some I kept closing and returning to because they were almost too flooded for me to absorb all at once. They were some of the most visceral connections I’ve ever witnessed in the time I have been writing this blog. I felt honored.

I picked ten folks that could feasibly come to my place on a random Sunday night, and ultimately the ten of us sat huddled around my laptop after dinner while Josh skyped in to talk to us from his Brooklyn apartment, shortly before he headed out on this long tour. Of course he was joyful, and of course he was thoughtful, and gracious. Most of us piped up with a question that had been on our minds after listening to the record — and all of us enjoyed his ruminations, his literary references, and his laughter.

Pull up a chair.

![]() JOSH RITTER ALBUM CLUB CONVERSATION

JOSH RITTER ALBUM CLUB CONVERSATION

March 10, 2013

Josh Ritter: Can I just say first of all, you guys, this is really awesome, I’m so honored, so honored. Thank you so much for doing this — this is incredible.

Heather: Oh man, we think it’s pretty exciting. I was thrilled to get a chance to do something where we get to actually get together in person and talk about music. We were just talking about how so many of our communities are not physical communities, so we don’t get to actually sit down and talk about things that matter to us, music-wise. We’ve all enjoyed even just already tonight having food and talking and all that. So thanks for giving us the opportunity to do that.

We’ve got a couple questions that different folks have come up with, and we thought we’d just start in, if you’re ready.

JR: Yeah, totally.

Maddy: So, Josh, with So Runs the World Away, you talked a lot about your writer’s block before that and how hard you were working to just consume music, literature, museums, get inspirations from wherever you could – feed the monster, as you said. Then with this album, it seems like you got inspiration that you didn’t want, internally, and I was wondering what you were also consuming, what you were reading, what you were listening to, while you were going through the process of writing this album.

JR: What I’ve noticed about writing records (and it’s not too much different from other things in life, I think) is that you’re so influenced by the external surroundings, but you’re most influenced by the choices you made on the last thing you did, you know? And with So Runs the World Away that was just …those were big songs. I had the compulsion to really write big songs, but also, I felt like I needed to put big things in my brain, you know? Like with songs like “Orbital” which was a song that I wrote just trying to…I just wanted to get “the big bang” into a song. I wanted to figure out the process, see if I could get it as concise as I could.

That was something that was really fun to do, but it also kind of felt frantic — like I was a stopped-up bottle and then suddenly I was free and trying to get as much written as I could at one time, really frantically. And that was without a personal external pressure. There wasn’t anything going on in my life that I knew at the time that was really pushing me in that direction. I just wanted to make something big, just because I thought it would be fun. And I felt that the album before, Historical Conquests had been kind of a scrappier thing; I wanted So Runs the World Away to have a little bit more orchestration to it, you know? So the museums, and the books I was reading at the time, that really helped me to do that.

With The Beast in its Tracks, obviously I was thinking very much about this major event in my life that was the catalyst for all this writing. You’re right, that experience really threw my influences into stark relief. The things that really mattered to me at the time, I went back to them like comfort food, you know? I went back to some of the writers that I really loved for a dose of what they had given me before….like definitely Flannery O’Connor. Or, also Fleetwood Mac — Fleetwood Mac was a big thing for me because I felt like — there’s a guy, Lindsey Buckingham. He can write a guitar line that has two notes in it, and it’s so badass. And he plays three notes and he’s gone, like that’s it. And I liked that kind of unselfish playing. I loved reading …I went back and read Deadwood, which is a book that I really loved, by Pete Dexter. I was also reading this book called The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, which was so good, mostly because I was interested in just that pace of the life. That book got me interested in other things in life besides what was going on in my head. To read about somebody who was interested in everything in the world, and had some really tragic things happen to him, but he still just pointed himself forward, you know? I guess the actual experience might be a catalyst, but it doesn’t give you a new vocabulary, it just realigns the vocabulary that you already had.

Seth: So, the great folk songwriters write great stories, and it’s not usually about their own life, but they look at the world around them and they respond to it, and they tell the world’s stories. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I think I read in an interview where you said you haven’t in the past really liked writing autobiographically. And wondering…this album seems obviously very much an autobiographical album, and wondering what gave you the freedom to put that hat on, so to speak, or to begin writing, opening up that door to yourself as far as what poured into the songs. What was that process like, if there was a process?

JR: I have to write about stuff. For most of my life, I’d been writing about the things I thought about and the things I saw, and I pictured this album kind of like walking across the desert and everything’s going fine – and then suddenly, you come to the Grand Canyon. So you can write about anything, but then you come to the Grand Canyon, and it’s undeniable and it’s right there, and if you turn around and you don’t write about it, you’re kind of a coward. You’ve gotta do it.

This is an important experience. So many people have it, it’s not just my own experience. And I would never write about it if it was just my own experience. It’s something that lots of people go through; a broken heart is something everybody goes through, so I just wanted to write about it in the way that was most open to everybody, while still being able to make sure I could tell the things that really mattered to me. But it was definitely a decision. I thought the idea of sitting down and writing about other things was so unthinkable to me at the time. I feel like after a while, of course, the power of that sort of stuff goes out, because you can only tell so many stories about yourself; you have to tell other stuff. The last thing I want to do is really bore people with that stuff. So I feel like this is a pass. I gave myself a pass in this one regard.

Seth: George Oppen said “Like a bull in a china shop: it is striking for a while. After that, the china shop becomes a bull pen, and the bull is an ordinary bull.”

JR: (laughs) That’s great!

Jon Jon: I have one that kind of follows up on that. Since this album is more autobiographical, and since you’ve only been singing these songs more recently, how has it affected your shows? Because now you’re coming out and feeling things — maybe you don’t feel them at that moment. Are you sort of like a method actor and you get yourself inside those past emotions, and if so, does that make your life more hurtful? Because that would seem like reliving painful moments night after night would be really hard. Are there ever songs you can’t play or anything like that, just because you’re feeling them so strongly?

JR: There are times when I feel that songs are super important to me in the moment, onstage, but it always sneaks up on me. Sometimes it becomes very emotional, but I’ve never been one to feel like I can let the song totally control me in those moments. When I’m on stage and singing, my body — I just go to sleep, in a way. Any pains or aches or anything you’re thinking about for the rest of the day just disappears. It’s an amazing thing that I think happens to a lot of performers. I’m really lucky that it happens to me, because singing songs every night has to be a new experience; every time it has to feel real and new, and the only way for that to happen is for you to just go into that kind of trance. And it’s not even an arty-farty thing, like it’s real — it’s a real trance moment, and it’s the most fun thing being up there, which is why I really enjoy singing a song like “Kathleen” even after ten years, it’s just so much fun and so enjoyable.

With these songs, I had my say when I wrote them and when I recorded them. And now when I play them, my responsibility is to play them really well and to play them in a way that people can relate to them. I feel like you spend a lot of time working on your recipes and trying them out, and then when you open the restaurant you want everybody to enjoy the food, you know what I mean? It feels that way. I want these songs to feel good and to be fun, and also to be useful, to be whatever people want them to be. When I’m on stage, I have to play them as powerfully as I can. Or hey, maybe I’m just talking crazy, maybe they will affect me. Maybe when I see you at the Ogden, or whatever, I’ll be just a wreck!

Heather: Have you played these songs a lot yet?

JR: I’ve played them a little bit, I took the band up on a small tour of kind of the Eastern seaboard and Canada to try them out. I don’t want to be the guy that plays the entire record in a night, because I know that there are a lot of songs that people would like to see…we want to play other songs too. So I want to make sure that if the new songs fit in, they fit in well, and that we fit the right ones in at the right times, so they just feel like part of the gang when we start playing them.

Ben: Hey Josh. So, we’ve all heard a lot of breakup albums dealing with similar circumstances, but I feel like yours is one of the few that comes out pretty uplifting for going through such a tough time. Were there times when you were writing this album, or when you started out with this process that you were writing more …vengeful songs? If so, when did it turn into the result, because I feel this record comes out on top.

JR: Yeah. That’s a really good question. I think first, partially, it was a question of “What do I feel good playing?’ The other thing was that, while I write songs for me, I also can’t help but see the other people that will eventually be in the room when I start playing it. I feel the weight of saying something that is really true. I want to see if it feels true to me. When I first started writing after all that stuff went down, I was writing really angry, angry songs — really mean, vengeful songs. They weren’t any good, they were just terrible — they were badly written, they were full of thrashing around. It’s just like if you were to throw an angry Chihuahua in the water. It was like that, and I could feel it, but as I wrote them they were a way to feel like I had some sort of power in what had happened to me.

As time went by those songs just kind of sat there and I knew they were no good, but I still felt like I had an attachment to them. So what Sam (Kassirer) did, my producer, he said “You just clear the deck and come up and record, and we’ll record all that stuff.” And we did. And just hearing it recorded and seeing it the way it was, that was useful just to get it out of the way. That was approaching on catharsis, and putting those songs to rest and kind of saying “Yeah, these are no good” was important. Getting those out of the way really made it possible to do what came next.

Heather: That’s a good answer. I think that’s good to think of it as getting it out and getting it out of the way, and that Sam was able to see the need to do that, and that you trusted him enough to get that out there and do it, and see what happened to it, you know?

JR: He’s an amazing guy, he’s was really generous. He knows I don’t want to be a mean guy.

Heather: Nope. You don’t.

Em: Hello. So I feel like most of your stuff before, like Bringing in the Darlings, was told from “Josh the storyteller”, and this is more of you as a person on this album. So do you think that’s your new voice, or was there a way you could have gotten all of this out and still had the same outcome for yourself, telling it more from a storyteller sort of way?

JR: I don’t think I could have, you know? I think there are people that can. And I certainly think there’s this tradition of really great storytelling …I think Bruce Springsteen can tell beautiful stories like “The River” — he just tells these stories so well, even though they didn’t necessarily happen to him. I had spent all this time writing these “larger” stories in songs, and it ended up becoming something which I’m really happy about but that couldn’t have gone on any longer. I think I was starting to feel the fray of that pretty hard. Because it limits you in some ways — things can only get bigger and more ornate, and stories can only get more complicated, and then suddenly they become dissatisfying, or they become too long for a song.

So I really think I got to that point with So Runs the World Away, and I didn’t really know what else I was going to do, and then that stuff came along and knocked the wind out of my sails and made it kind of impossible to write about any other stuff. Other stories just pale in comparison to your own story when it’s happening, you know what I mean? It’s more fun to wallow in your own story than in some other story. I think this might be the beginning of some new stuff, although I don’t think about it as necessarily autobiographical, so much as like… there are great albums like Wildflowers, that beautiful Tom Petty record, or Time (The Revelator), a Gillian Welch record, which aren’t autobiographical, but have a beautiful personal voice to them, without being larger stories.

Jon Jon: I have a question from Faith –who wasn’t able to make it– she said congratulations on the baby, and she was wondering how that has changed your outlook on life and your perspective, and how that has maybe changed your music?

Heather: And full disclosure: Jon Jon, who’s asking the question, is expecting his first baby in July.

JR: Oh congratulations, man!

Heather: Get ready to not sleep, ever!

JR: Yeah, I didn’t know what to expect. But, I think Haley [Tanner, author, and Josh’s partner] and I have both felt that there is this given narrative about doing music or art or whatever: that in exchange for this chance to make art, you have to give something up – a stable family life, a happy mental life, whatever. And it just — it can’t be. That narrative can’t be true. I feel like you can’t make great art if you’re truly, truly unhappy. The tortured artist is a horrible place to live, you know? It doesn’t give it any more weight or power. Why should any of us who take a chance doing something we love have to give up a chance for a family? I really believe that. It was definitely scary and freaky to think about.

We’re packing up right now and we’re all gonna be on the road in a few days, baby and all. But I think the things that have changed for me, just in these four months since Beatrix was born, I was noticing how my approach to writing has changed. My enjoyment of it has gotten so rich, in that short while. I used to sit around for six hours, like a little prince on a cushion thinking my thoughts, you know? And I don’t have time for that anymore. If I have time to write now, or if Haley has time to write, it’s at most like an hour. But you have tons of time to think! When you’re just walking around rocking her, and you have an idea you can’t write down, you have to hold it in your head, and it rolls around in there like marbles and it gets better and better and better. So when you have that hour and you have one crystal thought, you write it down when it’s perfect. And when you lie in bed exhausted at the end of the day, you can put a pin in it and say “I did that today!” That’s a much more rewarding experience. You may only be able to write one page of a book, or whatever, but a single page now is like gold!

Heather: I think it also changes the stakes, too. When you have kids and you’re doing something creative, the ability and time to be creative is filtered through fire, in a way. You have to fight to dedicate time towards what it is that you’re creating, and you have to really believe in it to carve out a space for it.

JR: Totally! Absolutely! I absolutely agree!

Betsy: So for me on this album, the song “New Lover” was what hooked me into the entire album. And I think it’s because it was the first song I heard, and it was maybe the most honest piece of songwriting I’ve heard in a long time. I was wondering if for you, if there was a certain song or a certain time along the process where it kind of hooked it for you, that this was going to become an album, and that you were maybe writing songs more with the thought in mind that ‘this is going to be a finished product’ that you would eventually tour with and record?

JR: Yeah! That song was “New Lover” for this record! That’s awesome that you thought that. Yeah, I was sitting at my friend Ed’s house, and I was working and writing all these horrible songs that sounded terrible to me. And then “New Lover” came along and I wrote it in the morning. It was still wintertime, but it was one of the first nice days of spring, and this song felt like it came out really fast. I was so proud of it, it was startling to me! It felt I accidentally found a way through the woods and through the emotions, to say — okay, it can be mixed, things can be mixed. Nothing has to be all one way or the other. Our love and our heartbreak, and all that stuff is mixed. It’s never the same thing. It’s never all the same thing all the way through. It’s like, here’s something I wish you could’ve done better, here’s something I guess I misunderstood, and it was my fault and I apologize. And that it can all go through in that complex way.

That was the first time I thought “Well, I could actually have a record here.” That moment happens for me with every record. With the last record, it was “The Curse”, with the record before it was, uh, I think it was “To The Dogs or Whoever” and then like Animal Years, it was “Girl in the War,” and then “Snow is Gone.” There always seems to be one song that feels like it gives you the kind of “pow” of stuff that you’re looking for, then you can take that apart and kind of explode it a little bit.

Abby: Yeah, I have a question! So we’ve talked about sort of different writing influences, and different voices between albums. I’m just curious what writing looks like right now, not just holding the baby and getting some words out at the end of the day, maybe, but actually the mental process?

JR: Sure! Right now when I’m writing, I feel pretty infused, pretty happy. I’ve written some other stuff that I’m just fishing around for, collecting feelings and ideas. Right now I’m really working on my new book, which I’m really excited about. In terms of restraint, the new book is completely unbound and nutso and it’s really fun — written with real happiness.

With Bright’s Passage, I was very much saying, “I think I’m actually going to be able to do this!” This book feels like I’m not worried about being able to get done with it. Right now, I’m just loving it – the feeling of creation, right now it feels like nothing has a bad consequence. I’m enjoying just the act of making something. I’m not worried about anything, we’re all healthy, everybody’s good. I can’t remember a time in my life when I was ever having a such a fully good time writing. The new book feels very biological and fun and sloppy, with terrible language (laughs).

Heather: I have a question for you, Josh. When I was setting up Album Club and getting the entries and reading all of the emails, I was bowled over by how many deeply thoughtful, really heavy, dense stories I got from people who wrote to me their thoughts about how your music had connected with them and what your music had meant to them at very difficult grief-filled hard parts of their life. You do realize that you’re inviting that on yourself even more with this record?! Like – how do you…I don’t even know what my question is, other than just I’m interested to hear what your perspective is on that deep connection between your music and real-life stories that people let you enter into, that you get to play a big part in. That must be pretty overwhelming?

JR: I think that, you know, when I listen to music, it’s medicine. It lets us…we take it when we need it. Sometimes it’s around us and we can’t avoid it and we can’t escape it. But most of the time I feel like those of us who love music and are active music listeners, we find it when we need it, you know? And it has to be for a reason. It has to be because there’s something in that particular music that we need, physically in our lives and in our heads for that moment.

I know for a fact that there’s times when I’ve needed to listen to Lucinda Williams or Tom Waits or even Marian Anderson, whoever it is. You don’t know why you want them, but you want them really bad, over and over. We’ve been on a Dolly Parton kick in our house recently. She does something to us right now that must be important. So I think that if you’re lucky enough that you’re making music and people find it useful, that’s what it should be! It should be useful. And if it is, then that’s just the highest praise. It really is. And it’s amazing that it happens.

Maddy: This isn’t a question, but just so you know, I think one of the most impressive things about this album is compared to a lot of breakup albums…a lot of that kind of songwriting can be helpful in that it validates feelings are universal for everyone sometime. And for this one, you do a really good job of doing that, and also offering hope or the ability to imagine something better, which I think is not something that is frequently accomplished with this, and I think makes it all the more powerful.

JR: Thank you! Thanks a lot. That’s amazing, thank you very much.

Mackensie: Last question. What is The Beast? And how do you kill or get rid of The Beast?

JR: Well I’m thinking again of that Teddy Roosevelt book that I loved, and I really responded to this thing he said: “Black care rarely sits behind a rider whose pace is fast enough.” And I thought that is so true, and I needed that so much in that time. You’ve got to keep moving, in hard times more than ever — just keep moving, keep doing stuff. The Beast is really this looming sense that when the sun goes down, your brain is gonna go. You’re gonna melt down. You’re gonna melt down. You can either melt yourself down, or you can keep on moving forward. During that time, I did all kinds of crazy stuff. Some of it was really bad.

I wrote a whole other book, which was a book about a guy trying to make his way across the country and it was ridiculous and weird, and it makes next to no sense. But I was writing it so fast because I was just trying to do stuff. And those songs that I wrote in that time, those were songs that were just trying to keep one step ahead of that feeling that my life was over, and that thing that I really believed in was a lie. I know that that’s not the case now, and of course I would not have believed that for long, but at that time it was hard not to sort of feel that maybe, there was a small suspicion.

So, The Beast is just that feeling of kind of heartbreak and desolation and giving up. I saw a sign somewhere that said “Stop the Beast in its Tracks” and I loved that. I love it.

Heather: Well, Josh…we love you, buddy. We’ll let you go pack for tour, and thank you, so much, for taking this time with us. I love that we could all get together and connect, and most of these people I hadn’t met before tonight. Thank you for giving us a space to do that. I think this is a wonderful thing.

JR: This is awesome. You guys get home safe. Thank you for paying me this huge compliment!

Come see Josh Ritter in Denver with the Album Club on March 27th, and then pretty much everywhere else on God’s green earth in the coming months.

[Thanks to Kevin Ihle for chronicling Album Club in photos, and to the terrific Em for help with transcription as well.]

F/F: The only other theatre adaptation like this that I’ve ever written about on Fuel/Friends is Spring Awakening, when I went to

F/F: The only other theatre adaptation like this that I’ve ever written about on Fuel/Friends is Spring Awakening, when I went to

WORKS PROGRESS ADMINISTRATION INTERVIEW

WORKS PROGRESS ADMINISTRATION INTERVIEW

Name: Heather Browne

Name: Heather Browne